Russia’s shadow fleet: a growing threat

In response to restrictive Western sanctions, Russia has built a shadow fleet to transport its oil. Global Insight assesses tactics used by the vessels to avoid detection and efforts by authorities to counter the fleet.

A tanker broadcasts its position in the Black Sea, near the coasts of Bulgaria and Romania. But a satellite image shows the vessel isn’t there; in reality, it’s hundreds of miles away near the Russian port of Taman.

The ship is one example of many identified in recent years as broadcasting false position signals to hide their movements. While motives are often unclear, vessels in the global shadow trade use location spoofing to avoid scrutiny by authorities or insurance providers over their shipments and sources of cargo. Kyiv School of Economics estimates that since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Moscow has spent over $10bn on building a shadow fleet to circumvent restrictions placed by the EU, UK and US on Russian crude oil and other related products.

Bjorn Bergman is a data analyst at environmental non-profits SkyTruth and Global Fishing Watch, working on a project to track false location signalling by tankers globally. ‘One thing we typically notice with falsification are repeated geometric patterns in the vessel track’, says Bergman. ‘It’s pretty obvious what to look for and know that the track is falsified since these patterns don’t show realistic vessel movement.’

Oil and gas exports have long been essential to Russia’s economy, traditionally accounting for approximately 40 per cent of its revenues. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, authorities in the EU, UK and US have sought to constrain Putin’s ability to finance the war, banning the import of Russian oil and introducing a price cap to prevent Western businesses from facilitating the transport of Russian crude oil sold above $60 a barrel. The mechanism is designed to force Russia to sell its oil at a lower price while avoiding a spike in global energy costs.

In response, Russia has sought new markets and built a shadow fleet to bypass the restrictions. The fleet consists of a growing number of aged tankers that are not owned or insured by companies in the G7. Poorly maintained and operating with minimal regard to international regulations, the ships present serious environmental, safety and security risks, including major oil spills. Russia has built the fleet mainly by transferring ships from its state carrier to new management companies abroad and purchasing second-hand tankers from sellers willing to exchange them for a discounted price.

Bruce Paulsen, a partner at Seward & Kissel in New York and Membership Officer for the IBA Maritime and Transport Law Committee, says that the rise of the shadow fleet calls into question whether the oil price cap was an effective policy decision. ‘The price cap policy itself did create a division between operators who play by the rules and this parallel infrastructure,’ he says.

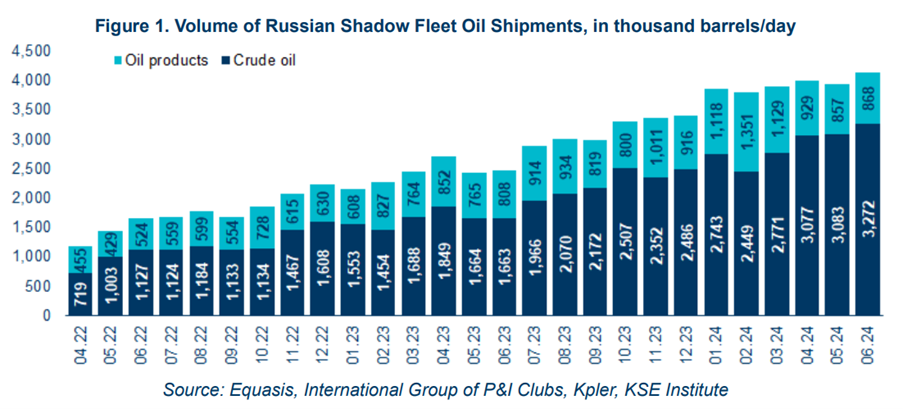

In a report published in October, Kyiv School of Economics said the volume of oil being transported by Russia’s shadow fleet is growing and in June reached 4.1 million barrels per day. The school estimates that 70 per cent of Russia’s seaborne exports are transported by the shadow fleet and in the first nine months of 2024, earned Russia an extra $8bn in oil sales.

Thomas Biersteker, a professor at the Geneva Graduate Institute, says that the EU, UK and US should have predicted all this. ‘Sanctions are very dynamic in this way like a game of tennis […] so you have to be constantly adaptable and flexible in the response to it’, he says.

Sanctions are very dynamic like a game of tennis […] so you have to be constantly adaptable and flexible

Thomas Biersteker

Professor, Geneva Graduate Institute

Biersteker says, however, that despite oil shipments by the shadow fleet increasing, sophisticated circumvention attempts by Russia are a sign that the restrictions are having an impact on limiting Putin’s funds to attack Ukraine. ‘The shadow fleet is more costly and difficult for Russia, I’m sure; if you look at the counterfactual of what they would have received without the sanctions, it’s in the tens of billions without a doubt’, he says.

The technology that tankers in the shadow fleet use to broadcast false positions in the ocean is called the automatic identification system (AIS). The system is used by ships globally to transmit data on identity, location, speed and destination. The International Maritime Organization requires vessels above 300 tonnes to broadcast AIS data on international voyages.

Russia’s shadow tankers use AIS blackouts or spoofing to hide entry into Russian ports or ship to ship transfers at sea, where oil is moved sometimes multiple times between vessels and may be blended with oil from other countries to obscure its origin. To conceal their activities further, the shadow fleet uses flags of convenience from countries that are less likely to enforce Western sanctions and have complex ownership and management structures to hide links to Russia.

‘The challenge with the shadow fleet is that ownership is very opaque’, says Gonzalo Saiz Erausquin, who is part of a maritime sanctions taskforce at national security think tank Royal United Services Institute. ‘Another issue is flag hopping, if a vessel is spotted to be flagged to one jurisdiction, it will just register with another to camouflage its operations’.

Countering the ghost fleet

Authorities in the UK, the EU and G7 have taken various steps to combat the activities of Russia’s shadow vessels. These include targeted sanctions on individual ships and increased international cooperation to disrupt their movements.

In June, UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer KC announced a call to action against the Russian shadow fleet which has now been endorsed by 46 countries and the EU. The agreement included an information sharing arrangement and a commitment to call on states to ensure ships flying their flag adhere to the highest safety and pollution prevention requirements.

In January, the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force, which also includes various Nordic countries and the Netherlands, launched an operation to use artificial intelligence to monitor Russia’s shadow fleet following reported damage to a major electricity cable in the Baltic Sea on Christmas Day by a Russian oil tanker. In an announcement about the action the UK government said it has so far designated 93 oil tankers suspected of helping Putin circumvent sanctions. Once on the UK sanctions list, the ships are banned from entering UK ports and British businesses cannot provide services for them under the oil price cap exception. Kyiv School of Economics found that in August two thirds of the vessels sanctioned by the EU, UK and US remain idle in the ocean.

Saiz Erausquin says, however, that while tactics such as disruption and designations make circumvention harder for Russia, the UK government is underestimating the value of strong enforcement against the companies and individuals behind the shadow fleet. ‘In the end, we’re just forcing them to another alternative structure or jurisdiction. We’re not necessarily ending that activity’, he says.

In the end, we’re just forcing them to another alternative structure or jurisdiction. We’re not necessarily ending that activity

Gonzalo Saiz Erausquin

Researcher, Royal United Services Institute

Enforcement of the UK’s financial sanctions regime, including the oil price cap, is handled by the National Crime Agency (NCA) for criminal breaches and the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) for civil violations. The UK Treasury told Global Insight that in August OFSI had opened investigations into 52 suspected breaches of the oil price cap by UK linked companies since the restrictions were introduced. Of those, 37 investigations were live and 15 had concluded. Neither the NCA nor OFSI, however, have yet prosecuted or fined a company or individual for breaching the price cap.

It is unclear how many of these investigations have involved businesses suspected of wrongdoing related to Russian shadow vessels. A spokesperson from the Treasury told Global Insight that it would take enforcement action over sanctions breaches ‘where appropriate’ and works closely in collaboration with its partners in the G7+ coalition. They said that data from Russia’s Ministry of Finance shows that there was a 30 per cent reduction in Russian government tax revenues from oil in 2023 compared to 2022.

John Bedford, a white-collar investigations partner at Dechert in London, says that, considering growing reports on the dangers of the shadow fleet and the strict reporting requirements on businesses and banks, the number of investigations opened into suspected price cap breaches appears low. OFSI gathers intelligence from a variety of sources including breach reports, foreign agency tips and whistleblower complaints.

Vladimir Putin, President of Russia

Bedford suspects any breach reports sent to OFSI are likely to be related to potential technical violations of the rules. ‘If you look through the conditions in the relevant general licence there are various attestations and similar requirements’, he says. ‘I suspect those sorts of technical breaches are the type of breach that have been reported to the authorities because if oil is selling over $60, it’s probably doing so in a way that’s not easy to identify.’

The oil cap coalition, made up of the G7+ countries, issued an advisory in October warning companies in the maritime industry about ways vessels in Russia’s shadow fleet are trying to bypass sanctions and access western services. They said that the ships often have undergone multiple ownership changes, rely on fraudulent insurance documentation and inflate shipping and ancillary costs to conceal the fact that Russian oil was purchased above the price cap.

Carl Newman, an officer of the IBA Criminal Law Committee, says that OFSI’s limited resources will make it difficult for the agency to identify who is behind opaque corporate structures and shell companies involved in the shadow oil trade.

‘It will require a detailed investigation that needs a lot of time and resources’, he says. ‘It can be an extremely complicated process to get to the bottom of who is behind a particular structure’.

Services Western companies could provide to Russian shadow vessels include bunkering, shipbroking and financial or legal services for entities that own the fleet. Saiz Erausquin says that the lack of enforcement actions may indicate that companies or individuals have self-reported and cooperated with OFSI about potential breaches and therefore the agency decided a fine wasn’t necessary. ‘We have to think that some of these breaches might happen after a lot of due diligence is conducted by the relevant actor’, he says. ‘OFSI might say, well, we investigated this breach, we confirmed it happened. We stopped it from happening further, because we've already engaged with this UK business that was involved. But we don't see really grounds for fining an entity that really struggled to find out that they were involved in a breach’.

Private sector engagement

Since the UK introduced oil sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, OFSI has worked closely with the maritime insurance sector to help it enforce the price cap. The British maritime insurance industry dominates the international shipping sector and insures about 90 per cent of the world’s vessels. Oil spill insurance, also known as protection and indemnity insurance, is required under international maritime law and without it, vessels cannot renew their annual flag registrations or conduct normal operations. Under UK sanctions rules, UK insurers cannot insure any vessels that transport Russian crude oil sold above the $60 per barrel price cap.

Giles Thomson, the head of OFSI, said at a Treasury Select Committee hearing in November that the insurance sector is generally ‘making incredible efforts to comply’ and that there has been ‘a large element of derisking from the market’.

Biersteker says that while UK companies restricting insurance cover appears to have been an effective way to drive down the price of Russian oil at first, because Russia has moved to domestic, other or no insurance arrangements for its fleet the inability to access Western providers will no longer be much of a deterrent. ‘Russia’s counter measures and response, increasingly, is to come up with alternatives that lie outside of those that are publicly known’, he says.

Paulsen believes it is only a matter of time before the world wakes up to the huge legal risks that the shadow fleet presents. ‘I think the big risk, and what the world is going to wake up to, is that there's going to be an incident, an environmental incident, and the ship that causes it is not going to have correct insurance,’ he says.

If the other ship doesn’t have insurance, then it’s quite difficult to make a recovery from that vessel

Mike Salthouse

Head of External Affairs, NorthStandard

A lack of legitimate insurance presents major challenges for insurers in the case of a collision. Mike Salthouse, Head of External Affairs at maritime insurance company NorthStandard, says a collision between a shadow vessel and Western ship would make it difficult to recover costs. ‘That’s a risk because normally, as in car accidents, there will be some sharing of liabilities but if the other ship doesn’t have insurance, then it’s quite difficult to make a recovery from that vessel’, he says. In July, a suspected Russian shadow fleet vessel reportedly collided with another tanker in Malaysian waters, causing both to catch fire.

Salthouse says one of the biggest problems with the Russian shadow fleet, besides sanctions circumvention, is that it has created a less well-regulated environment, which is likely to undermine the important safety work that has been adopted by the global shipping industry over the past 30 years. ‘That needs to be addressed […] the vessels that are actually trading in a manner that poses a risk to coastlines and safety’, he says.

Alternative approaches

International organisations and various experts have made recommendations to governments as to how to combat the shadow fleet. In November, members of the EU Parliament voted for EU Member States to enhance maritime surveillance, tighten shipping controls, increase designations of vessels and deny tankers transporting sanctioned cargo access to EU waters, particularly in the Baltic Sea.

Biersteker says that the EU, UK and US may increasingly turn to secondary sanctions to help enforce the price cap by deterring businesses and banks outside the G7 from trading oil with or facilitating sanctions circumvention by Russia. ‘We have seen an evolution from primary to secondary sanctions […] that is the dynamic we are in now, I think it’s less focus on the price cap and more on the secondary measures’, he says.

Kyiv School of Economics recommends that the US use the threat of secondary sanctions to discourage companies based in non-G7 jurisdictions from selling retired or aged tankers to Russia’s shadow fleet. The school also recommends the creation of ‘shadow-free zones’ by excluding shadow fleet tankers without industry standard oil spill insurance from G7 waters and designating those that fail to provide requested information.

Kyiv School of Economics estimates that three Russian shadow tankers per day pass through northern European waters, including the Danish Straits and the English Channel. Most travel unnoticed while carrying millions of gallons of thick black liquid loaded from Russian ports in the Baltic and Black seas. ‘A major environmental disaster is only a question of time’, the school warns.

Alice Johnson is the IBA Multimedia Journalist and can be contacted at alice.johnson@int-bar.org